In 1959, Morio Kasai, a Japanese surgeon discovered a breakthrough in the treatment of biliary atresia which had a poor survival rate before. The procedure which carries his name, although modified in various forms, is still performed today for patient's with biliary atresia.

Procedure

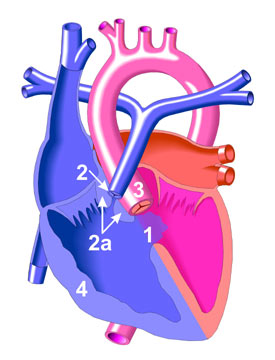

The principle of the procedure is the resect the atretic parts of the extrahepatic biliary tree, dissect the porta hepatis of the liver to free up patent biliary ductules and anastamose with the intestine in a Roux-en-Y fashion (portoenterostomy).

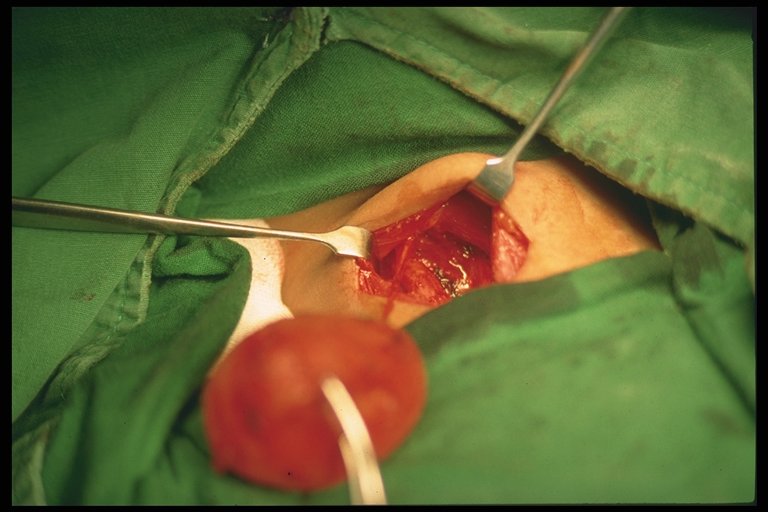

A right upper abdominal incision is made (though from my observation here, the roof top incision is popular). Other anomalies should be sought out and excluded (polysplenia or asplenia, malrotation, preduodenal portal vein, interrupted vena cava).

Before dissection of the portal plate (porta hepatis at the liver surface), examination of the extrahapatic biliary tract is made. If the gallbladder is atretic and without lumen, the surgery may then proceed with the Kasai. If not, an on-table cholangiogram must be performed to delineate the extend of atresia or if atresia exist at all. Failure to outline patent intrahepatic and extrahaptic biliary structures justifies the need to proceed with portoenterostomy.

The hepatoduodenal ligament (the free edge of the lesser omentum) is opened up to identify the structures of the bile duct and is dissected away from the hepatic arteries. Dissection is continued proximally towards the liver, the gallbladder also dissected. The end-point of dissection is after the bifurcation of the portal vein. A fibrous cone and portal plate should be seen here.

At this stage, the fibrous cone should be transected with knife or scissors. This is the most

crucial step to the success of surgery, too deep a cut will cause injury to the liver and cause subsequent scarring and obliteration of the biliary ductules. Too superficial, patent biliary ductules are not exposed enough for drainage. The use of

diathermy should be discouraged as this may damage the fine ductules that is essential to the success of the surgery. Care is taken to not injure the portal vein to avoid bleeding.

The proximal jejenum, about 10 cm from the Ligament of Trietze is identified and transected. The distal end of the transection is anatamosed with the liver with 6/0 absorbable sutures brought through the avascular portion of the mesocolon. End-to-side jejunojenunostomy is created at about 50 - 60 cm from the transected part of the jejunum. The defect in the mesocolon is closed by anchoring the roux limb. This is done to prevent internal herniation and keep the limb without tension.

Placement of a suction drain is recommended by some near the portoenterostomy site.

Post-Op

Return of 'color' to stool is an indication of success which usually occur after 10 - 14 days. However some will still progress to liver failure despite initial cholic stool, and some remain with acholic stool.

NG tube is continued until about 48 hours post-op.

Recommended medical regimen includes:

Choleretic: Ursidol : 10 - 15 mg/kg/dose bd

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) : 2.5 mg/kg/day

Vitamin ADEK

Prednisolone : 2mg/mg/day to be tapered down over 6 weeks.

Factors to Success

Age of surgery seem to be an important factor. Most literature report success if the procedure is performed at

70 to 90 days old. This however

does not contraindicate surgery in older children.

Patent gallbladder and fibrous cones are also indicators to better prognosis. So does the diameter of ductules.

Complications

Cholangitis:

An important complication that may lead to the next devastating complication, portal hypertension. Prevention is best done by performing an adequate roux surgery, as well as antibiotics prophylaxis during surgery and post-operatively. The use of steroids also helps in reducing inflammation that may also prevent scarring of the liver although presenting evidence is controversial (not discussed here). Otherwise, treatment is best done with broad-spectrum antibiotics that covers anaerobes as well.

Portal Hypertension:

The usual triad may form including ascites, hypersplenism with associated thrmbocytopenia, and the feared esophageal varices that may lead to bleeding. Liver transplant is indicated if this complication is severe.

Intrahepatic biliary cavities of cyst:

May develop within the liver that may contribute to recurrent cholangitis. Larger ones may be drained percutaneously.

Others:

Wound dehiscence

Internal herniation through the mesocolon defect.

Anastamotic leak

Intussuception at the foot of the roux.

Malignancies:

Cirrhotic liver may lead to hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatoblastoma which all have been reported in patient's with biliary atresia.

References:

1.

Coran, Arnold G., et al., Pediatric Surgery, 7th Ed., Elsevier

2. Wildhaber, Barbara E., Biliary Atresia: 50 Years After the First Kasai, Review Article, ISRN Surgery (2012). Must read. Contains other articles on modified Kasai procedures and others.

Future Topics:

Biliary atresia

Liver Transplant

Complications of biliary atresia (in details)